Bitrate: 256

mp3

Ripped by: ChrisGoesRock

Artwork Included

Source: Japan 24-Bit Remaster

Jonathan Kelly will be familiar to some of you as the Irish folk singer who made waves in Britain in the first half of the 1970s, following an apprenticeship on the Dublin scene in the previous decade. His absence from the charts, and his disappearance after 1976, has hidden his story from the mainstream while at the same time fostered a cult following for the handful of albums he recorded. To call him a folk singer is to miss the broad progression of his style, from whimsical pop through lush folk and unexpectedly delving into funk rock late in his career. One characteristic of his song-writing, which remained remarkably consistent through all these changes, was his finely tuned social conscience. As frontman of The Boomerangs in 1966, at a time when his contemporaries were singing about lovely girls and hucklebucks, Jonathan’s first single, ‘Dream World’, instead looked at Cold War tensions and the hope that “east and west did reunite / and Mars did cease his endless flight.” Earnest without being pretentious, Jonathan’s lyrics became increasingly angry and political during the next decade before abruptly halting at the peak of his talents. There’s more to his story which can be found elsewhere, but this article will look at his still-relevant and still-stirring lyrics on war, religion and inequality.

Jonathan Kelly was really Jonathan Ledingham from Drogheda. Although he never addressed it directly during his recording career, it seems his experience as a Protestant growing up in a Catholic state left him somewhat alienated and perhaps gave him an outsider’s perspective. At the end of 2013 a new CD collected demo versions of unreleased songs recorded during his years in musical exile. One of these songs, ‘Eileen’, recounts the pressure of having to separate from an early sweetheart because of religion: “I was your secret boyfriend when you were just seventeen. / Eileen, my sister was right when she said we could never be, / I was all in orange and you were all in green” (incidentally, Jonathan’s manager informs me that he is still trying to track down the long-lost Eileen, who worked at a department store in Dublin). Another recent song, ‘I Wanted To Be’, states: “I lived in a land where I never belonged, / where I was mistreated and where I was wronged.” He added in a 2006 interview, “I just looked around the world as a young man, I saw all the institutions that I was told to revere, religious institutions and nationalist institutions, and I saw so much hypocrisy and so much self-pleasing and so much violence and hatred” and “I began to question the rather racist teachings that I received from older people in my growing and nurturing environment regarding people of other races who were meant to be inferior, that certain nations were better than others and that war is justified.” Finding an outlet in Rock & Roll, Jonathan played guitar or drums in several short-lived bands, including The Saracens and The Boomerangs. Already influenced by protest singers like Bob Dylan, Jon Ledingham embarked on a solo career with his 1967 single ‘Without An E’ (the odd title apparently refers to the lack of an E string on his guitar) and ‘Love Is A Toy’ in 1968, also writing songs for Johnny McEvoy, The Johnstons and The Greenbeats. The B-side of ‘Love Is A Toy’ was ‘Thank You Mrs. Gilbert’, a jaunty anti-war song worthy of Donovan, in which an army officer writes a letter to the mother of a new recruit: “He says that he is fighting for peace throughout the world. / It’s an interesting thought, though it’s really quite absurd. / He’ll soon find out the reason why we have so many wars. / Without them our economy would fall right through the floor.”

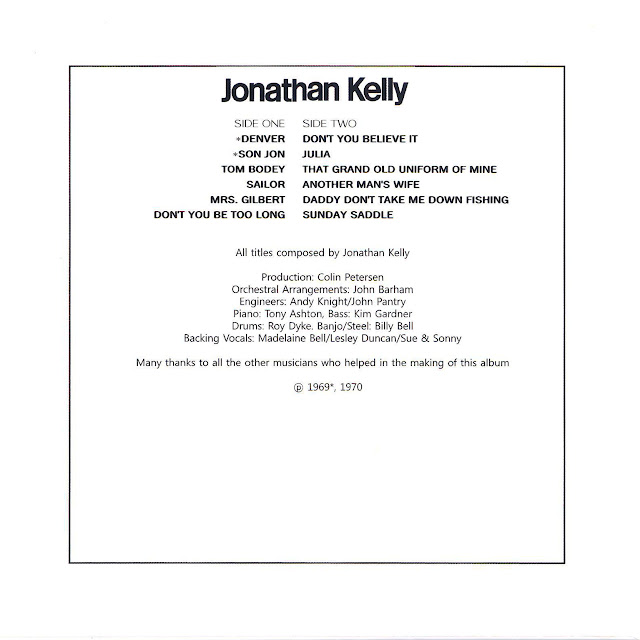

Jonathan’s self-titled debut album featured many of the earlier single sides, including a new version of ‘Mrs. Gilbert’, and was a mixture of protest and pop. Among the new tracks was ‘That Grand Old Uniform Of Mine’, written from the viewpoint of a conscripted soldier: “If only everyone from home would write me everyday, / when I return I can kid myself I’ve never been away, / and that’s the day I’ll celebrate and watch the flames grow higher / from that damned old uniform of mine.”

The contract with Parlophone ended here and Jonathan spent 1971 gigging and writing before returning with the ‘Twice Around The Houses’ LP, released on RCA in 1972 (after a deal with Warner Brothers fell through). His writing had matured greatly in this short time and tracks like ‘Madeleine’, ‘Sligo Fair’ and the wonderful ‘Ballad Of Cursed Anna’ would prove to be some of his most popular and enduring songs. Elsewhere, ‘We Are The People’ contained his most directly political lyrics to date: “Do you hear the brass band playing? / Do you hear the tramp of feet? / Twenty thousand working men / are coming down the street. / Will you listen to what they’re saying? / Will you listen to their song? / One man may not be right / but can all of these be wrong?” It has been suggested that the lines “now I hear the prison walls / are growing without relief / for locking up people without a trial, / jailed for their beliefs” are in reference to internment in Northern Ireland at the time, although Kelly’s political standpoint was by now more concerned with radical socialism rather than nationalism or patriotism, which he equated with “bloodshed and violence”. In the frantic ‘The Train Song’ he seems to takes a subtle dig at religion with the line “I was friends with the vicar, his mother and son, / till one day I rolled up with a time machine gun / and blew them all back to around 20 BC / to show them the traitors that they’d turn out to be.”

1973’s ‘Wait Till They Change The Backdrop’ continued in the same style, blending ballads like ‘Down On Me’, the folk fairy-tale ‘Godas’, and more pointed material such as ‘Turn Your Eye On Me’, in which he characterises political leaders who, forty years later, are still sadly familiar: “Heard of a man, lost in his notions, / sent out his bombers far across the oceans / to kill and to maim his brothers and sisters. / What you doin’? What you doin’ to me, mister? // You make the poor on this world pay / for how you live and what you say. / Only time you make your move / is when your business friends approve.” ‘Turn Your Eye On Me’, ‘Down On Me’ and other tracks on this album notably featured Gary Moore on guitar. After this it was time for another change in direction. Quoted in ‘The Bee Gees: Tales Of The Brothers Gibb. (2009), Kelly recalls separating from his management: “Colin and Joanne were different to me; different, different, different! They loved the fame and glory and being in the midst of the pop industry. I hated the pop industry actually. I saw it as totally ruthless and callous.” He goes on to recount an incident where a restaurant owner was giving his partisan opinions on the Arab-Israeli conflict to Kelly and the Petersens: “they weren’t political at all, I don’t think they thought politically. I did! I couldn’t help it, and this guy was talking all this racism at my table… I said, ‘Can you please go away from this table’. I will not sit joined to somebody who is talking racial hatred… But I was awkward and a troublemaker and I understand from their point of view that was a real problem.”

To mark his new direction he formed the group ‘Jonathan Kelly’s Outside’, with Chas Jankel (later of Ian Dury & The Blockheads) on lead guitar, Trevor Williams on bass and Dave Sheen on drums. Perhaps surprisingly, it’s The Blockheads’ gritty British funk that bears the closest resemblance to the music of ‘Outside’ (although Jankel was replaced by Snowy White, later of Thin Lizzy and Pink Floyd, before their album was completed). In fact, Jonathan had been nurturing a love of funk music for some time and cites Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, Herbie Hancock, Miles Davies, Curtis Mayfield, Sly & The Family Stone and Funkadelic as big influences on this period of his career. Released in early 1974, ‘…Waiting On You’ (a personal favourite) features an inner illustration by Tim Staffell and some wonderfully passionate funk rock on tracks like ‘Sensation Street’ as well as the plaintive, Van Morrison-esque, ‘Great Northern Railroad’. It also marked the high point of Jonathan’s social commentary. ‘Misery’ takes on workers’ rights and predicts revolution: “Working all our lives / getting coal dust in our eyes / spending all the days God gives us underground. / We can’t live on what you pay. / You make us strike so you can say / ‘They’re beggars trying to bring this nation down’.” ‘Tell Me People’, meanwhile, scornfully confronts a range of issues, from war (“The leaders watch you fight it out but their blood never spills. / Think of all the children, born of love, their hatred kills. / Tell me people, ‘specially brothers, what are you gonna do? / You gonna let those sons of darkness make a killer out of you?”), religion (“Tell me preacher, what is your plan? / Is it really for Jesus Christ that you stand? / You say that love is infinite and all souls are as one, / but then you preach division in the pulpit Sunday morn. / Remember when your leader kicked the short change across the floor? / Today the church is wealthy but the people still are poor.”) and poverty (“Someone tells you charity is better kept at home, / so you set up all your boundaries and you keep it for your own. / By day you serve the nation and you cause prosperity. / By night you sit at home and watch the famine on TV.”).

At a low ebb personally and financially, and disillusioned with both politics and the music industry, Jonathan lost interest in performing in 1976 and took a job in a London record store, although his official website (which preserves a vast array of photos, clippings and flyers from his time in Drogheda and Dublin) notes that he played drums for the group ‘Instant Whip’ in the Phoenix Park around this time with Tim Booth, Ed Deane and Steve Bullock. Looking back on his time as a professional musician via the same website, Jonathan reflects, “I hated capitalism. How could an artist do his work for monetary reward? Art is unselfish and seeks no reward save the joy of creating works of art that are honest and innocent of greed and done only to add beauty and reason to our beautiful earthly home.” Jonathan recalls what happened next: “A man came to my door and said ‘I’m looking to talk with people who’d like to see a change in the world. What I mean is, an end to war and poverty and hunger. Do those things concern you?’ I said, ‘Come in.’” Despite his previous animosity – “I certainly didn’t think religion had any answer, in fact, like many people say today, I saw religious institutions of the world as being the most reprehensible element in the whole universe, for the hypocrisy of them.” – Jonathan became a Jehovah’s Witness and found some of the peace of mind he had been looking for. “You see, when you find the answer to all your questions, why go on searching anymore?” As Jonathan Ledingham, he started a family and a carpet cleaning business in rural England. He effectively vanished until tracked down by long-time fan Gerald Sables in 2002, who reconnected him with his die-hard fans and persuaded him to come out of retirement for a series of small solo acoustic shows between 2004 and 2008, following which he returned to his private life.

This renewed activity, and CD reissues of Kelly’s RCA albums, led to talk of a new Jonathan Kelly studio album, but as those plans seem to have been put on ice, the ‘Home Demos’ collection was released a few months ago with demos of the new songs recorded over recent years. On these, Jonathan’s youthful rage has largely given way to contemplation of life experiences. In ‘I’ve Been Down That Road You’re On’, he remembers, “So you join the revolution, you’re tired of sitting on the fence, / you never did like the bourgeoisie and all their fake pretence / so you join the cause for freedom and you start setting up some tents / and learning the philosophy and it all makes so much sense / till your friend comes ’round and says ‘here’s your guns and armaments’ / and you turn around to him and say I didn’t know there’d be violence.” Yet there remain flashes of his earlier moral outrage; in ‘No Words’ he describes seeing a man accused on TV of treachery to his country, and the ‘poisoned words’ used to condemn him: “I thought about that man, that revolutionary, / and his defiance in the face of a nations animosity, / and I thought of his accusers, seemed like church folk to me, / singing hymns and praying on bended knee, / and reading their bible and their liturgy, / but I don’t think they’ve learned a single thing, you see.” It seems that Jonathan’s current faith is based more on making a positive contribution to society through voluntary work than on joining the conformist establishment he had railed against in his youth; rather than doing a simple about-turn on religion he retains his deep ethical principles. Sables recounts that one of Jonathan’s oldest friends once remarked to him that “Jonathan was the most well balanced person I ever met….. he had a chip on both shoulders!” When asked if this was true, Jonathan replied, “Oh Yeah!…Still is!”

01. Denver

02. Son Jon

03. Tom Bodey

04. Sailor

05. Mrs. Gilbert

06. Don’t You Be Too Long

07. Don’t You Believe It

08. Julia

09. That Grand Old Uniform Of Mine

10. Another Man’s Wife

11. Daddy Don’t Take Me Down Fishing

12. Sunday Saddle

+

Jonathan Kelly - Twice Around The Houses (UK 1972) (@256)

01. Madeleine

02. Silgo Fair

03. Were All Right Till Then

04. Ballad Of Cursed Anna

05. Leave Them Go

06. We Are The People

07. Rainy Town

08. The Train Song

09. I Used To Know You

10. Hyde Park Angels

11. Rock You To Sleep

1. J. Kelly

or

2. J. Kelly

or

3. J. Kelly